Have you always wanted to know what really happened to our CPF? What did the government change over the years and what did they not tell you?

Today, I have compiled the most comprehensive history of the CPF, and how it has been intertwined with the Singapore economy, to such a huge extent that you will see here, that a lot of the problems that we face in our lives today are actually linked back to how the government has tied the CPF into too many aspects of the Singapore economy. I have trawled through several books, academic papers and government websites to compile this for your one-stop convenience on the real history of our CPF, which the government has been lacking to educate on. Please do spend some time to read this.

Most importantly, you need to know how Singaporeans have been made to shoulder the burden of the current problems – because it is YOUR CPF that the government is using.

(Much of the credit also goes to Mukul Asher, Linda Low, Phang Sock-Yong, Lawrence B. Krause, Yasue Pai and many others who have been quoted in this article on their research and analysis.)

So here goes. It is a bit long and I have divided the article into eight pages. But this is a really important article. Please do take some time to read this, or bookmark it and come back to read the later pages. It is really important that you read this because you will know how your life is being affected by how far the government has over-stretched itself, to over-extend your CPF for their purposes.

CPF was Started by the British in 1955

By now, you would know that the CPF was started in 1955 by the British. The British was actually studying various pension systems, but opted to adopt the CPF system because “the mood at that time was that colonies like Malaya and Singapore would not be colonies for much longer” and “the British government had simply been quite firm in making a political decision not to be financially burdened with the social security plans of the colonies“. Thus if the British government had adopted the “unanimous recommendations for an insurance-based social security scheme” which was actually proposed by several committees set up to study the implementation of a social security system in Singapore in the 1950s, Singaporeans would be seeing a more holistic social security protection system for us today, which would include unemployment insurance, for instance.

Of course, when the PAP took control of government later on, they were quite happy with the CPF system. But why? The PAP was able to manipulate the CPF for their own uses – primarily to generate income for themselves.

CPF was Used to Finance HDB’s Construction of Flats

The first change came in 1968. Our CPF was legislated to become “a source of funds for the government as will be witnessed in the CPF as the Housing Development Board (HDB)’s financing agent“.

Indeed, in 1968, “The CPF became an important institution for financing housing purchases from September 1968“. The PAP government passed “legislation (which allowed CPF) withdrawals from the fund to finance the purchase of housing sold by the HDB and subsequently sold by other public sector agencies as well.“

Actually, prior to 1964, it was not the aim to get all Singaporeans to buy flats. In fact, the “original objective of the HDB … was to build flats for rental“. But then, the PAP government changed their objective to “selling flats to tenants in 1964“. And because asking people to buy flats did not take off, the PAP government thus “liberalised” the CPF and created the Home Ownership Scheme to let CPF be used “for the down payment and monthly instalments towards the purchase of public housing flats”.

But the CPF was also used to fund the HDB from broader level, which is lesser known to Singaporeans – “The CPF was the financing agent for the HDB at the macro national level and micro level of households, respectively and sequentially. First, at the macro economy level, the government borrows funds for development expenditure through the development fund before it built up budgetary surplus.” And “In the initial years, before the government built up budgetary surpluses, it borrowed funds from the CPF for its development expenditure budget – one important user being the HDB.” Thus “The CPF is clearly an important financial agent of the government whether from direct financing through loans as the CPF is mandated to invest its balances in specially issued government bonds or as indirect revenue generated through massive housing and ownership in all forms of real estate taxation and charges. A third micro financing modality is when CPF members drew down their savings to purchase housing.

As such, “The HDB obtains two types of loans from the government budget, one as contribution to public housing, and the other for mortgage financing,” “interest of which is pegged to the prevailing CPF savings rate. The mortgage lending rate charged by the HDB to homeowners is 0.1 percentage point higher than the rate that it borrows from the government,” which is said to ensure “the sustainability of the financing arrangement.“

In short, “CPF funds were lent to the Housing Development Board so that it could build flats“.

The government borrowed the CPF to finance the construction of HDB flats, then asked Singaporeans to use our CPF to “buy” the flats.

The PAP Government Increased CPF Contribution Rates to Finance the Construction of More Flats

Now, the CPF started off solely as a retirement fund and thus initially, the CPF contribution rates were low and only a small portion of our wages needed to be deducted. “At the time of its introduction in 1955, the CPF contribution rates were 5.0 percent for employer and 5.0 percent for the employee, for a total of 10.0 percent.” However, with the PAP government’s new plan to extend the CPF “to support the(ir) national home ownership drive“, “in 1968, the government raised the CPF contributions by employers and employer from 5% to 6.5%” and “with just three increases starting in 1968, the contribution rate reached 10 percent by 1971, which was double the original rate. By 1974, the CPF contribution was 30 percent of a member’s salary.” The PAP government kept increasing the contribution rates until they “peaked at 25 percent of wages for both employers and employees from 1984 to 1986“.

In fact, in just a short span of just 7 years, “annual CPF collections increased more than four-fold from $46.9 million to $223.6 million between 1965 and 1971.“

But why did the CPF contribution rates kept increasing upwards, from 10% in 1955 to 50% in 1985? By 1985, Singaporeans had to pay half our wages into the CPF! Why did the PAP government want so much money? It was said that, “Such a high savings rate is evidence of the intent to make CPF more than a pension scheme for retirement,” as indeed can be seen in how the PAP government has extended the CPF to be used for HDB construction.

But how else?

The Over-Use of CPF for Housing Contributed to the 1985 Recession

Notably, in 1982-83, there was an “unprecedented” growth in total overall construction of residential buildings. In fact, “the increase in public-sector (HDB) residential building construction was itself unprecedented … The number of units of residential buildings under construction jumped to 94,000 in 1982 from 59,000 in 1981; a record 77,000 units of residential buildings were completed in 1984, more than double that in 1983 and in any year in the seventies.“

However, because of “The acceleration in public housing (HDB) construction in 1982- 83, (this) was considered by Krause to have been excessive in that it contributed towards ‘over-heating’ of the economy and the property slump and recession which followed in 1985-87. The Property Market Consultative Committee also similarly concluded that “the rapid increase in public-sector construction contributed towards the over-supply in the property market“. Indeed, 189,000 HDB flats were constructed during the Fifth Five-Year Building Programme when the original target set in 1980 was for the construction of 85,000 to 100,000 flats“.

It was asked, “did the acceleration in public housing construction serve other than a growth objective – in view of the fact that 1984 was an election year and a year for celebrating twenty-five years of achievement?” To that, “Krause et.al. (also hypothesized) that the acceleration in public housing construction (indeed) served other than a growth objective – 1984 being an election year as well as a year for celebrating 25 years of achievement as an independent nation.“

In fact, Lee Kuan Yew later on admitted in his memoirs, “We made one of our more grievous mistakes in 1982-84 by more than doubling the number of flats we had previously built.”

Yet why did Lee Kuan Yew so vehemently pursued the housing programme then? Goodman, Kwon and White explained that he “believed that if people owned their own homes, they would be more likely to ‘fight the country“.

Indeed, Lee Kuan Yew had said in ‘From Third World to First: The Singapore Story 1965-2000:

My primary preoccupation was to give every citizen a stake in the country and its future. I wanted a home-owning society. I … was convinced that if every family owned its home, the country would be more stable … I had seen how voters in capital cities always tended to vote against the government of the day and was determined that our householders should become homeowners, otherwise we would not have political stability. My other important motive was to give all parents whose sons would have to do national service a stake in the Singapore their sons had to defend. If the soldier’s family did not own their home, he would soon conclude he would be fighting to protect the properties of the wealthy. I believed this sense of ownership was vital for our new society which had no deep roots in a common historical experience.

In other words, the HDB served as a social lock-in tool (for the citizens onto Singapore), whilst the CPF was used as the financial lock-in.

CPF Study Group in 1986 Asked the PAP Government to Stop Over-Extending the CPF for Housing but It Fell on Deaf Ears

In 1986, the CPF Study Group, recommended “that the authorities refrain from pursuing policies that would induce individuals to siphon more and more of their savings from their CPF to continuously upgrade their properties and to purchase additional properties, at the expense of other more pressing family needs and to the possible detriment of their ability to finance a decent old-age livelihood, besides contributing to inflating property prices.” They asked the government to restraint from the excessive use of the CPF to finance the construction of HDB flats.

However, the PAP government did not heed this early warning but instead did the “opposite” and “promoted the upgrading policy and (again) allowed the user of CPF funds for this purpose“.

The CPF Study Group had also recommended that “CPF members be allowed to opt out of making employee’s CPF contributions once a specified minimum balance had been accumulated, so as to give them greater freedom to use their money.“

Indeed, it was said:

The rate of contribution to the CPF should not be used as a macro-economic instrument to control inflation as it has important repercussions on the allocation of consumption and savings contemporaneously as well as over time. Since its main (and original) objective is to provide for savings for old age, the combined rate of contribution should be set at a level consistent with this objective, and it should be maintained at that level. The use of CPF savings for the purchase of housing distorts consumption patterns, as pointed out by a comprehensive study of the CPF. The fulfilment of the political objective of home ownership by increasing CPF contribution rates so that more funds would be available for this purpose is, if true, economically inefficient.

So, you see, way back in 1986, warnings were already sounded against over-extending the CPF for purposes other than for retirement as this would be “economically inefficient”. However, these warnings fell on deaf ears. And the Study Group also highlighted the pitfalls of manipulating the CPF contribution rates for purposes other than for retirement.

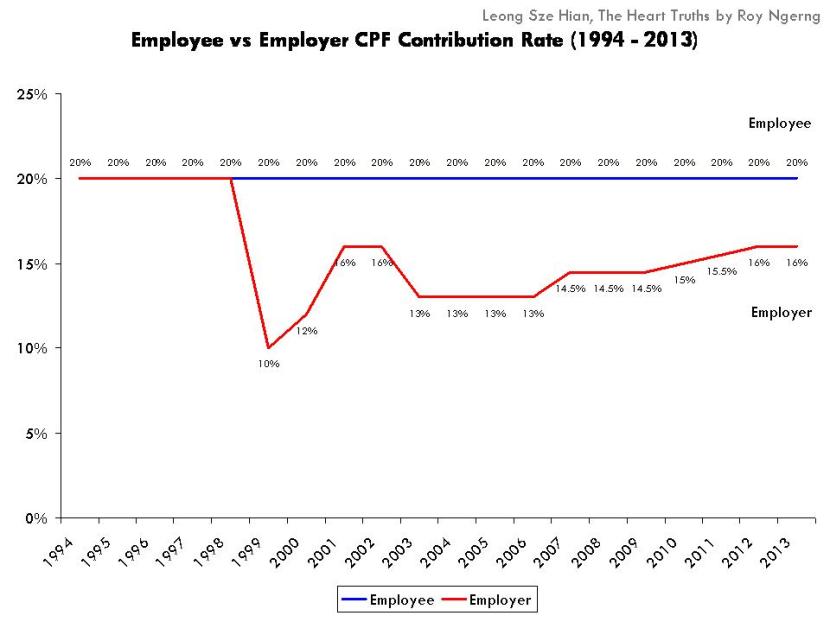

Instead of drawing back on manipulating the CPF contribution rates, the PAP government went against the committee’s recommendations. They kept the employee’s CPF contribution at 25% in 1986 and 1987 while only reducing the employer’s CPF contribution rate – to 10%.

In fact, the same thing happened again after the 1997 recession.

And because of such a lopsided policu, today Singapore is only 12, or one of the 7%, out of where employees would contribute more into social security than employers.

What caused the PAP government to ignore such warnings (way back in 1986 or nearly 30 years ago) to stop their compulsion with the over-use of CPF funds to artificially inflate housing demand and prices is beyond common-logic comprehension. But perhaps when it is known that “the public sector and its GLCs may account for 60% of gross domestic product“, one might understand why the PAP government would favour policies that benefit employers more, at the expense of Singaporeans, in spite of the recommendations.

The PAP Government Over-Built Again and the Housing Bubble Burst in 1997

But the problem of over-construction wasn’t confined only to the early 1980s. Clearly, the PAP government never learnt its lesson.

As the PAP government became ballistic in its compulsiveness to profit from the housing market, it once again over-built HDB flats. And yet once again, when faced with the recession in 1997, the PAP government became at a loss.

Then-Minister for National Development Mah Bow Tan admitted that, “when the Asian Financial Crisis hit in 1997, … HDB ended up with 31,000 unsold flats“. What’s more, it took the PAP government more than 10 years later to admit the truth in 2009.

Yet, Mah Bow Tan had the cheek to say that this resulted in a “waste of taxpayers money”, but as history has shown, who was the one who repeatedly made the same mistake, in spite of numerous warnings? And who was the one who continuously ignored these well-intended advice and went head-on with their addiction to (over-)construction?

When the PAP government under-constructed in the early 1980s and partly caused the recession in 1985, they were forewarned not to repeat the same mistake and not to over-indulge themselves with our CPF monies. But they did not heed the advice and allowed housing prices to spiral out-of-control again from 1994, over-built yet again and by 1997, over-extended themselves yet again, this time with “taxpayers money”.

Will the PAP government ever learn their lesson, or will the obsessive compulsive addiction to cheap money from our CPF to build flats for profit be too much temptation to resist?

Indeed, today we are seeing the built-up of yet another housing bubble and feeble attempts by the PAP government to stoppage a potential burst.

Join the #ReturnOurCPF Facebook event page here.

Roy Ngerng

*The writer blogs at http://thehearttruths.com/