Why are Singaporeans unable to save in our CPF? Why is it that we contribute 37% of our wages into CPF, but the CPF is still not enough for our needs?

Last week, some speakers gave presentations at the Forum on CPF and Retirement Adequacy (organised by the Institute of Policy Studies). Their presentations will give you a very good insight as to why the CPF is inasequate for Singaporeans’ retirement and in the problems highlighted, you can see the solutions inherent in them as well.

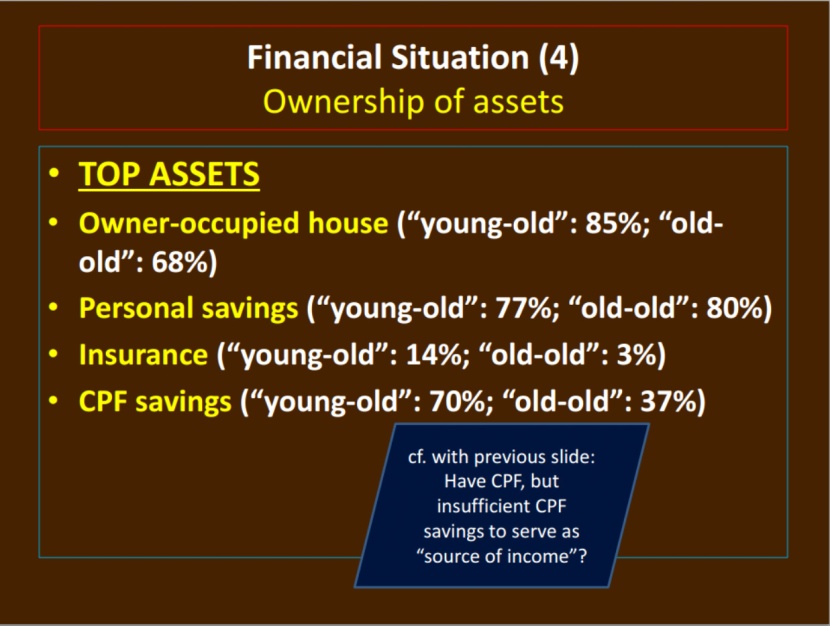

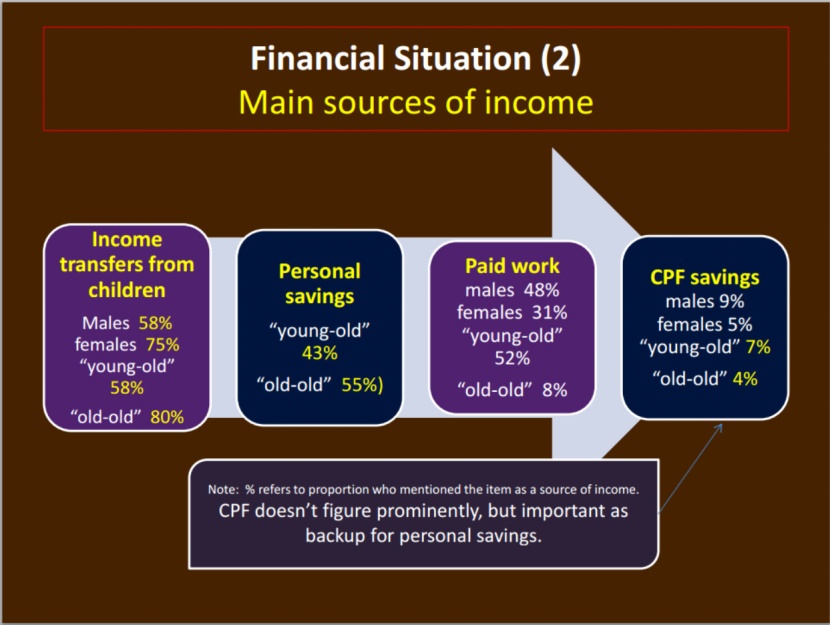

Associate Professor Tan Ern Ser illustrated that up to 70% of the elderly in Singapore have CPF.

However, he then highlighted how the CPF savings is able to provide for retirement for only a very low 4% to 7% of the elderly in Singapore. A/Prof Tan asked then asked how even though the elderly might “have CPF, but (do they have) insufficient CPF savings to serve as (a) “source of income”?”

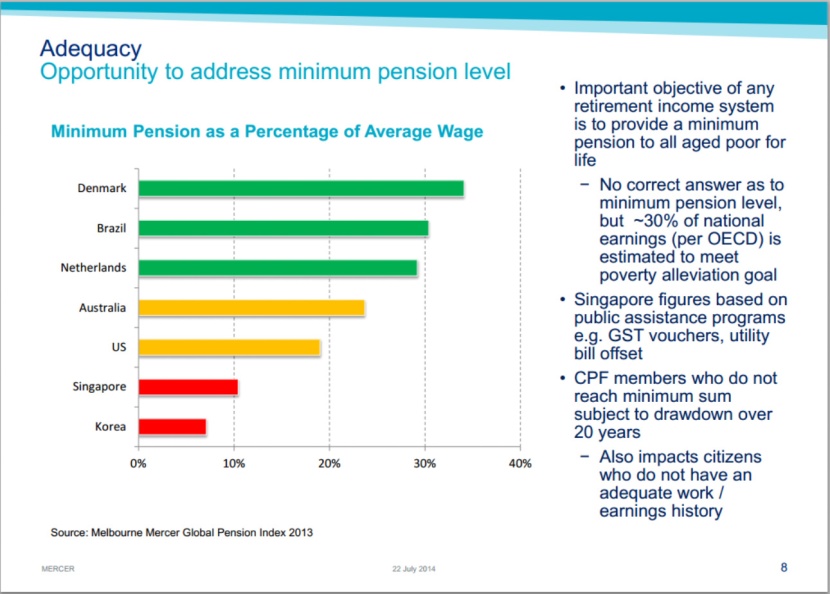

But why our our CPF funds inadequate? Indeed, Ms Wong Su-Yen then pointed out how in the Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index 2013, Singaporeans have been shown to have one of the least adequate pension in the world. She highlighted how a minimum pension level of 30% of national earnings would be the minimum required to alleviate poverty, but in Singapore, the CPF provides only 10%, which means that most Singaporeans would retire with payouts at below poverty level.

In fact, yesterday, I had calculated how 50% of Singaporeans would have less than $55,000 in our CPF and would only be able to get a CPF payout of $425 every month. This is significantly lower than (or only one-third of) the $1,200 that the government has calculated a lower-middle income family would need to have a basic standard of living. If half of Singaporeans have to retire on less than $425, it is clear that the majority of Singaporeans are retiring at below poverty level.

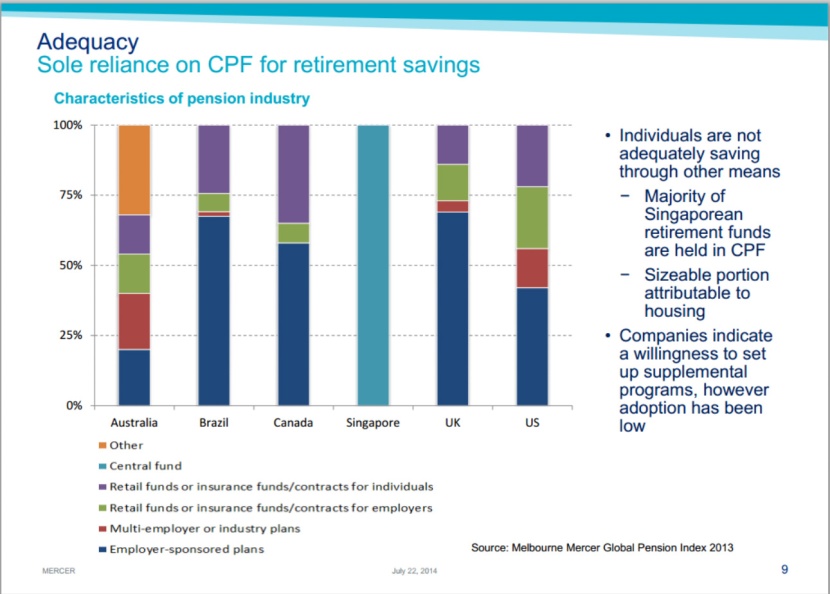

In fact, the problem is compounded by how the pension system in Singapore relies solely on the CPF, whereas in other countries, there is a diversification of sources for retirement savings, and which allows for a higher accumulation of pension funds.

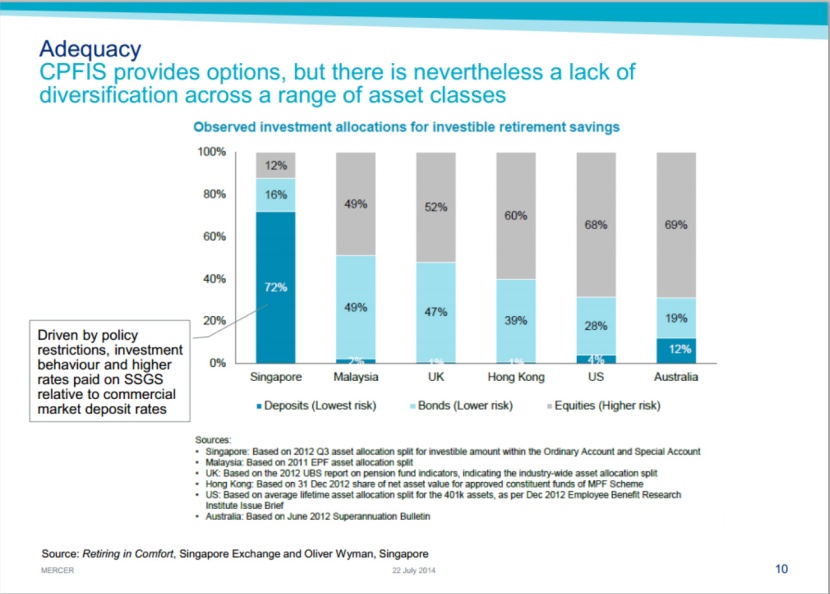

Ms Wong went on to highlight that the two key reasons why the CPF is inadequate. First, the CPF is over-invested in very low-risk deposits. 72% of the CPF is invested in very low-risk deposits while other countries would only invest up to 12% in similar deposits, and would instead invest 49% to 69% of the pension funds in higher risk equities, to earn higher returns for the pension funds and increase adequacy.

The government might claim that the current “CPF system”, where the government invests our CPF in low-risk government bonds and then take these bonds to invest in higher risk investments “has worked well and … protected members from risk.” The government claims that this “allows the GIC (to take on the risk and) to invest for the long term, including investing in riskier assets like equities, real estate and private equity.” But the evidence from other international pension funds have shown that they are very capable of taking on the higher risks by themselves, and returning the interests earned back to their citizens. So, why does the Singapore government act contrary?

In fact, Prof Mukul G. Asher has said that, “Singapore’s method of investing the balances meant for retirement financing is contrary to best international practices concerning pension fund management, and have the potential to generate high political risk. Such concentration of savings in the hands of non-transparent, non-accountable agencies also distorts the savings investment process and could lead to inefficiencies in the structure of asset returns. The development of the financial and capital markets may also be adversely affected due to such concentration of savings, and due to the use of CPF as a substitute for mortgage financing. The method, however, is consistent with Singapore’s mono-centric power structure, and strong tendency towards social engineering and control.”

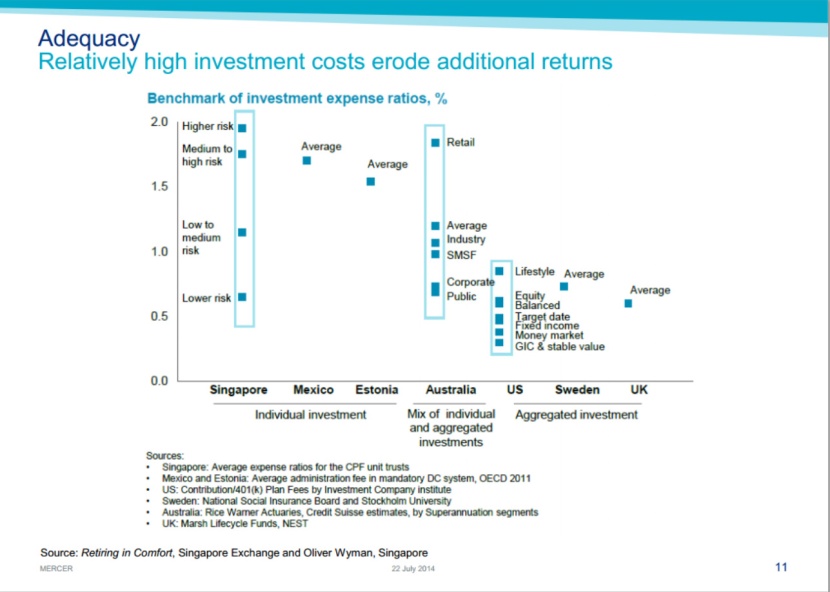

Second, the Singapore government charges the highest costs to manage our CPF, which “erode additional returns” and reduces what is returned to our pension funds. Which begs the question – why does the government charges the highest costs for managing funds invested in the lowest risks?

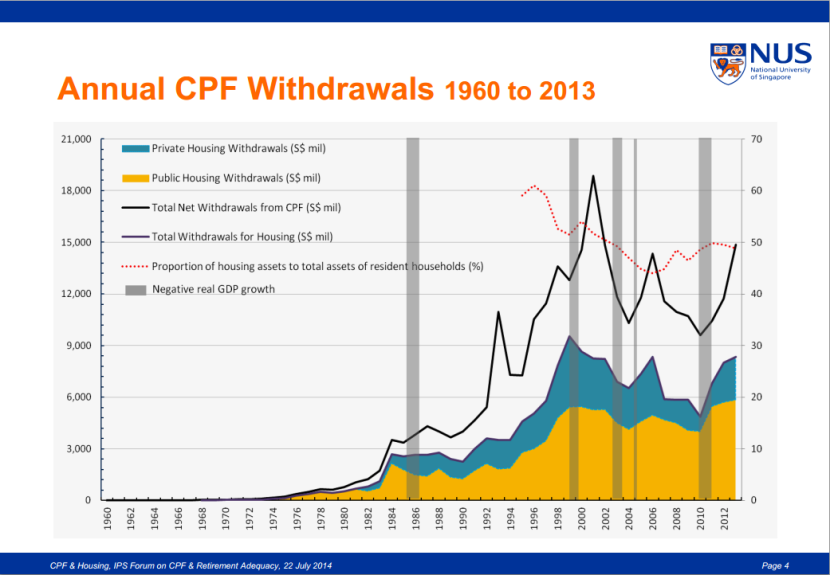

Ms Wong also highlighted how “Individuals are not adequately saving … (because a) sizeable portion (of the lack of retirement savings is) attribute to housing.” Indeed, this was what Associate Professor Lum Sau Kim also pointed out. She illustrated how the annual CPF withdrawals to pay for housing loans have been increasing since the 1960s, which has resulted in “low cash balances” inside the CPF which has “constrained retirement adequacy”.

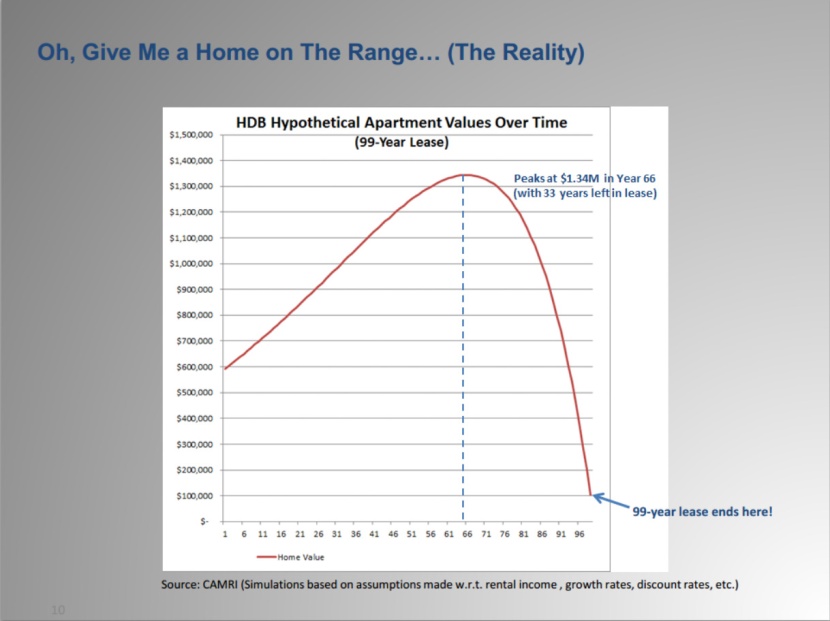

Professor Joseph Cherian also brought up an interesting chart to show how the HDB flat starts losing its value after Year-66 and eventually has zero value. Indeed, thanks to a question by the Worker’s Party Gerald Giam, we now know that “the value of the flats will be zero at the end of their 99-year lease” and “Like all leasehold properties, HDB flats will revert to HDB, the landowner, upon expiry of their leases.”

In fact, the National Development Minister Khaw Boon Wah had also admitted earlier this month that the government “controls the construction programmes” and “sets the prices for the HDB flats”. As such, when housing loans sap up a large portion of our CPF, so much so that Singaporeans are not able to save enough in our CPF to retire, then is it not clear that the government has over-priced the HDB flats?

Manpower Minister Tan Chuan-Jin has also revealed earlier this month that, “Among members who turned 55 years old over the past five years and had used CPF monies to purchase HDB flats, an average of 55% of their OA savings had been withdrawn to finance their flats at age 55.” For Singaporeans who had used their CPF to buy private property, this could be twice as high.

If so, from the above statistics, is it not clear that:

- First, Singaporeans’ CPF is earning too low returns.

- Second, coupled with the low returns on the CPF, the high flat prices further eats into the declining value of the CPF.

If so, these are the questions we have to ask:

- Who controls how our CPF is invested and how much returns to give on our CPF?

- Who controls the housing prices?

Why are they not letting us grow our CPF?

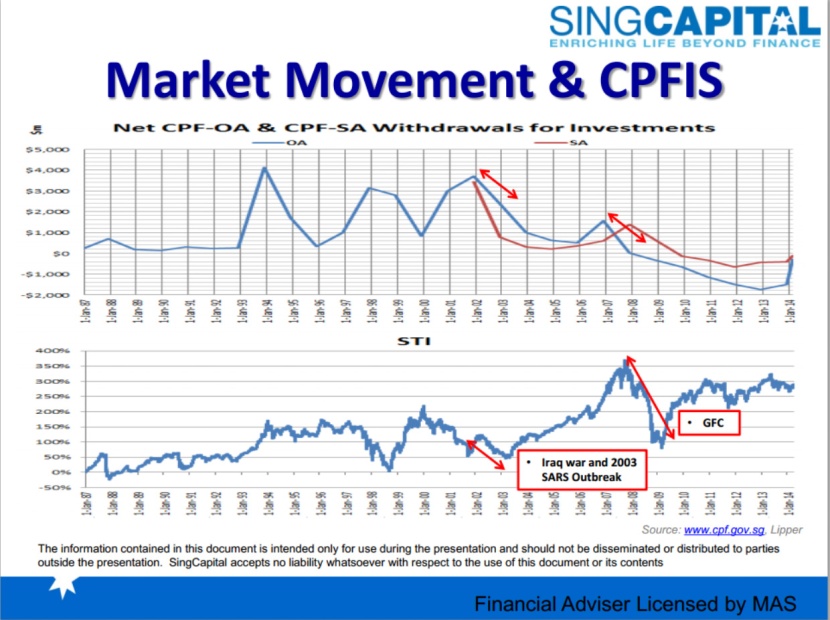

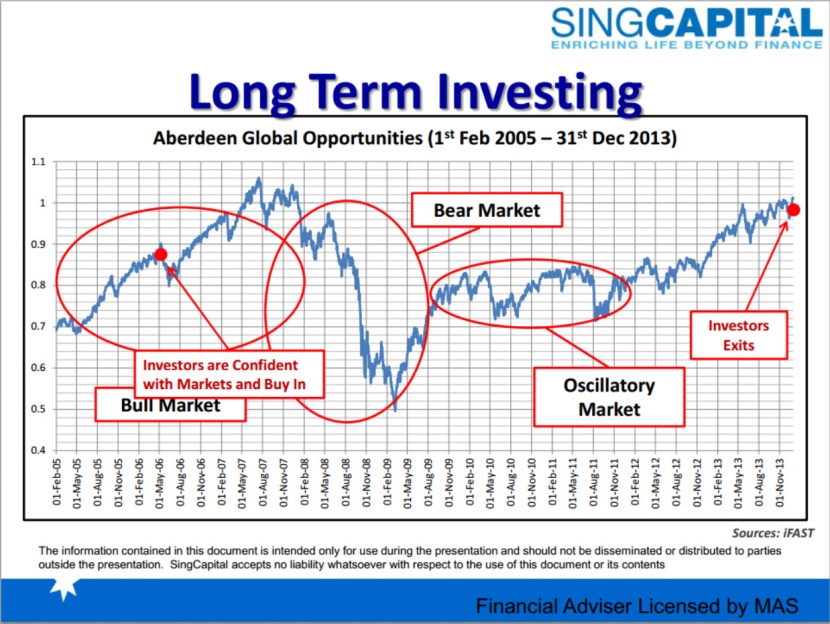

Mr Alfred Chia also highlighted how the CPF Investment Scheme had failed because these schemes were introduced “very close to when the markets were at its peak”, thus when the market fell right after, losses were made. (Was it bad policy introduction timing, or?)

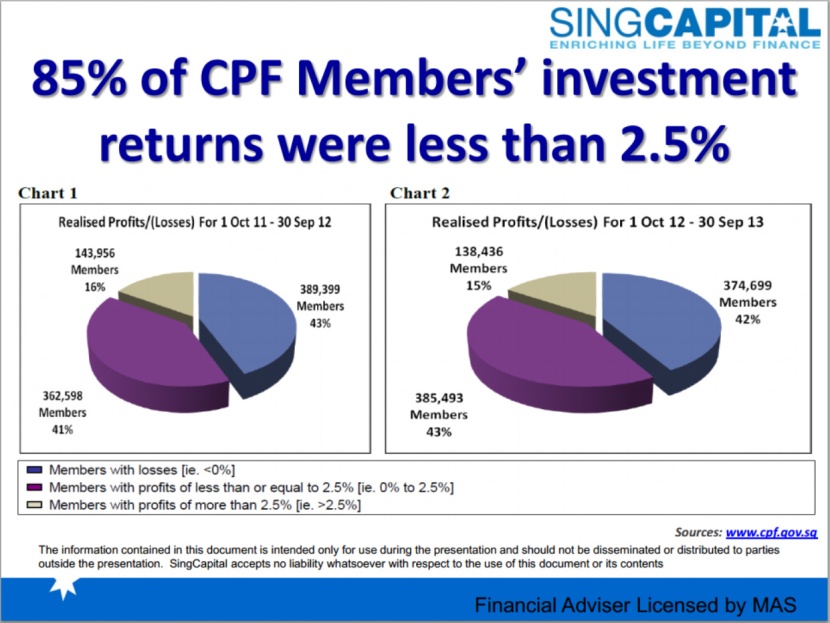

This explained why 85% of CPF members’ investment returns were less than 2.5%.

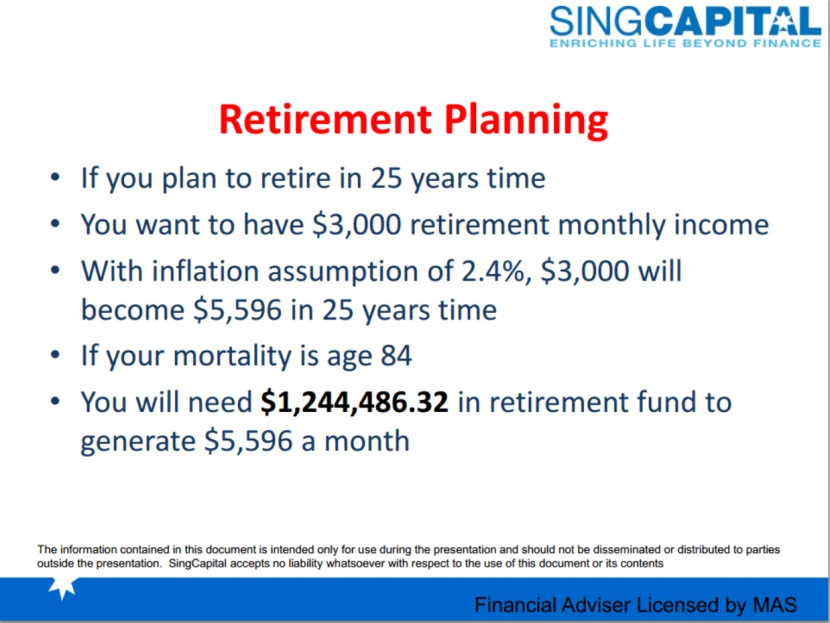

Mr Chia then illustrated how if a Singaporean wants to retire on $3,000 every month (or $5,596 in 25 years’ time), he/she would need to save $1.24 million at retirement.

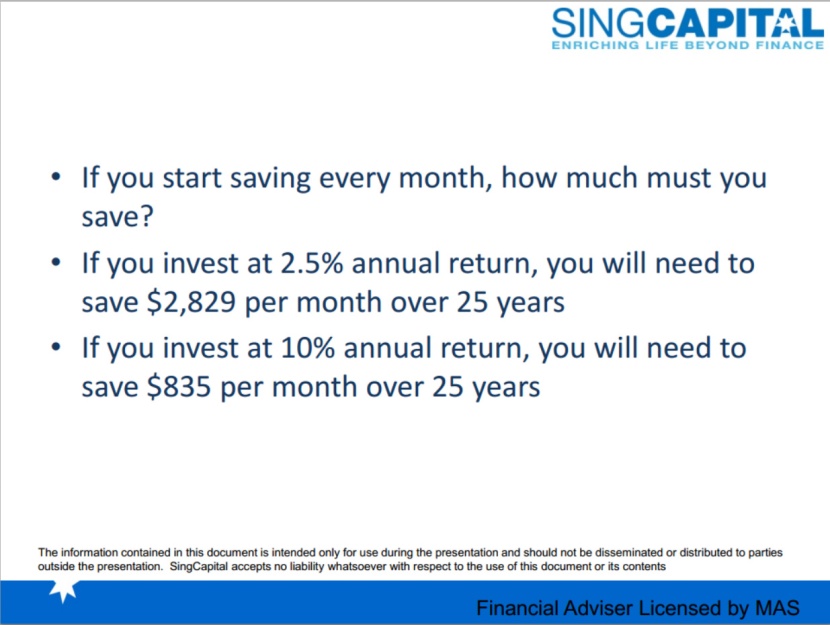

He explained that this means that at the current CPF interest of 2.5%, a person would need to save $2,823 every month for the next 25 years. This would mean that a person would have to earn more than $7,000 every month in order to do so! However, less than 10% of Singaporeans are able to earn more than $7,000 currently!

However, A/Prof Tan had shown that only 17% or more elderly Singaporeans spend more than $2,000 every month, so the magnitude of this problem is reduced. However, this still doesn’t negate the problem. Where half of Singaporeans are only able to withdraw $425, this is simply inadequate for the majority of Singaporeans. This also reveals that at current wages, Singaporeans would simply not be able to save enough in our CPF for retirement. Including for the current uses of the CPF, the minimum that Singaporeans would need to earn would be at least $3,000 or $4,000 to be able to save adequately in our CPF for retirement!

AWARE’s Vivienne Wee had also posed a question at the forum, where she commented that 40% of older women are not able to get employment and which are not able to give them enough CPF. She opined that this is why there are many women are not able to meet the CPF Minimum Sum, because they do not come under the scheme. Associate Professor Kalyani Mehta agreed that women are under-protected by the CPF and shared that the CPF system is not universal but this has not been acknowledged.

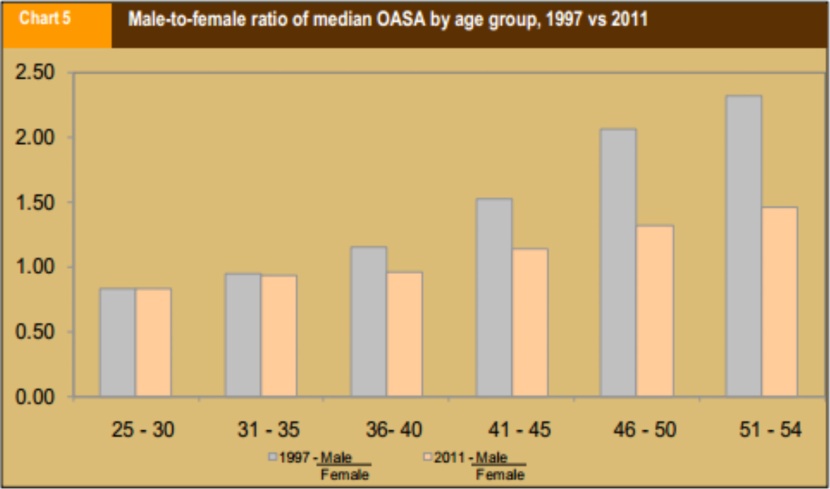

Indeed, there is a gender imbalance in the CPF system, in how women are able to save significantly less in the CPF than men (even though both are unable to save adequately).

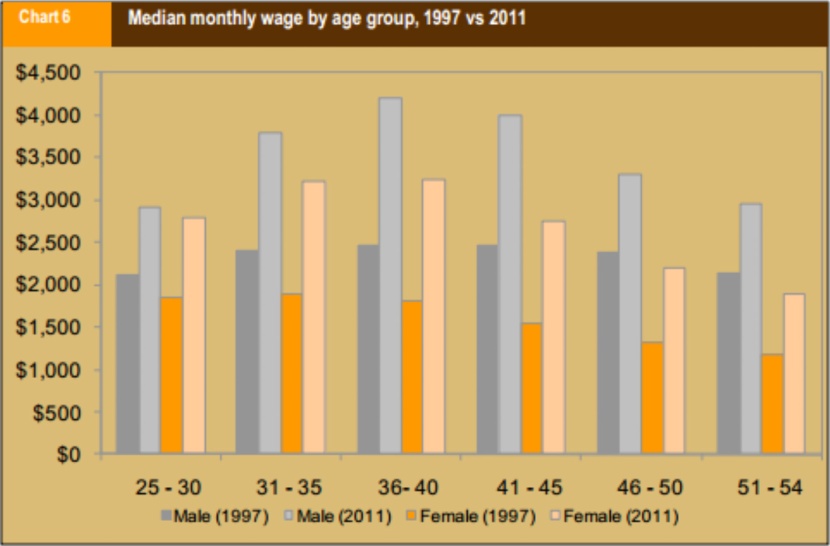

And women also earn significantly lower wages than men (even though both have seen stagnant wages over the past 2 decades).

A/Prof Tan had also highlighted how, “Female and older seniors are likely to be in low-paying jobs and doing less well financially.”

When seen in light of these problems, it is thus perhaps disturbing that both the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance and the Manpower Minister had claimed that the CPF is aimed only at providing for basic retirement needs. The Deputy Prime Minister went further to say that the government has been very clear with this all along and that the CPF is not intended to provide for the full retirement needs for Singaporeans.

However, where the CPF is only adequate for 4% to 7% of Singaporeans, and where up to 80% of the elderly have to thus rely on their children, is it not unsustainable? Already, Singaporeans are earning stagnant wages, and compounded by the stagnant CPF interest rates and ever-increasing housing prices, the real value of Singaporeans’ CPF have been so eroded that it can be said to have lost its purpose – this is quite clearly affirmed by how the CPF is only adequate for 4% to 7% of Singaporeans and is one of the least adequate pension funds in the world.

It is perhaps very disturbing if the government chooses not to acknowledge this fact but would bypass the existence of such problems, to claim the validity of the current CPF system. It might be perhaps disappointing for the speakers and participants at the forum.

The problems were highlighted, but so were the solutions. If the government has any political will to fix the system (instead of the opposition), we might actually make some headway in reforming the CPF system to bring about adequacy for Singaporeans’ retirement.

Prof Cherian had summarised what he thought was the current problems with the current CPF system.

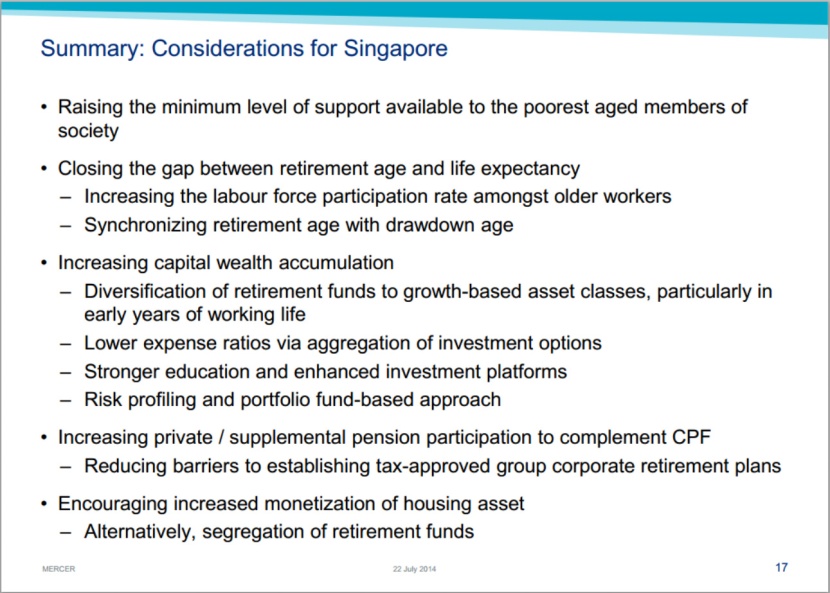

Ms Wong had proposed some plausible solutions.

Mr Donald Low advocated for transparency and independence of the CPF.

Perhaps the government should also take a leaf out of Mr Chia’s book, where he advocated looking long term when investing. As such, the government cannot continue the fear-mongering that they are giving us short-term “secure” interests, but should instead plan long term for higher returns for Singaporeans. As Prof Cherian had wisely put, “You cannot let people feeling worse-off because of an (economic) downturn. You have to plan long term.” As yet, the government has still not wanted to let Singaporeans know the GIC’s returns since its inception in 1981 (the CPF is invested in the GIC).

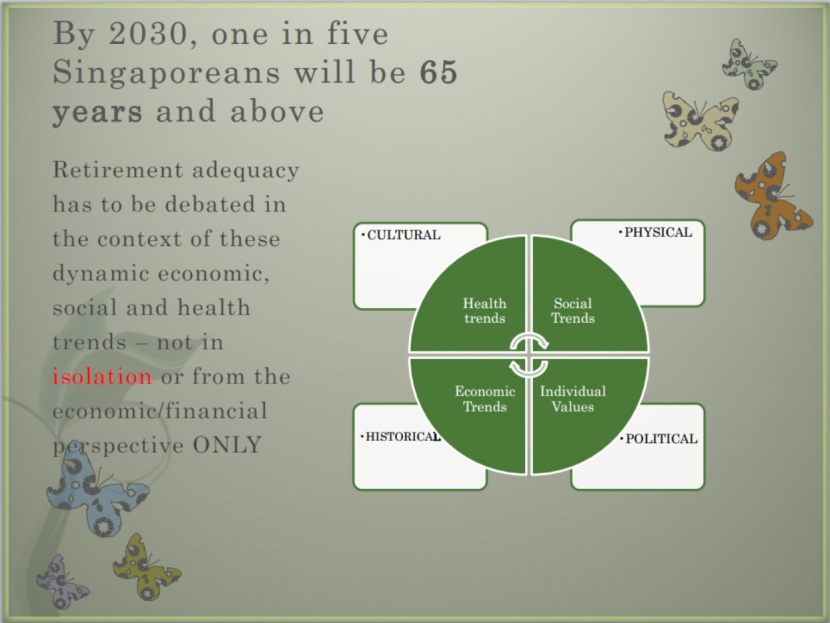

And finally, A/Prof Mehta affirmed the values that “Retirement adequacy has to be debated in the context of these dynamic economic, social and health trends – not in isolation or from the economic/financial perspective ONLY.”

So, you see, Singaporeans know what the problems of the CPF are. We know the solutions too. The question isn’t about whether we know the problems, but whether there is political will and the boldness to resolve these issues and bring about a reform to the CPF to bring about a betterment of Singaporeans.

Have we seen the courage to make the bold changes required for our CPF been shown by the government so far?

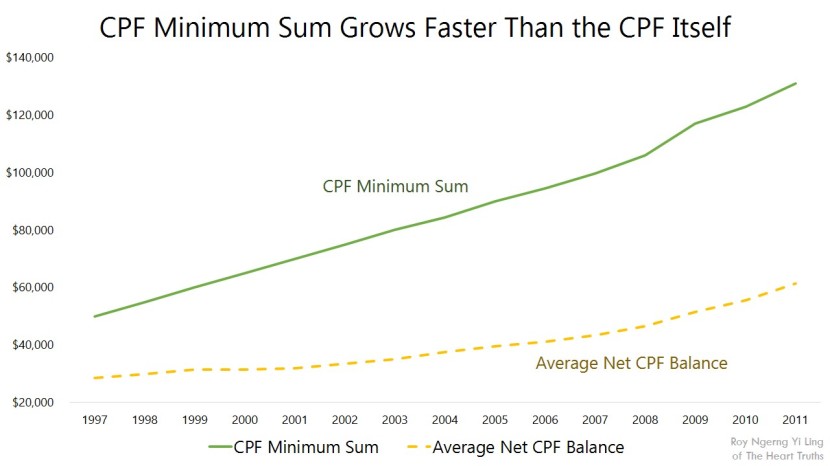

Instead, what we have seen is how the government continues to champion the CPF Minimum Sum and admonishes Singaporeans for not working hard enough to meet this CPF Minimum Sum. But when you realise how the government has been increasing the CPF Minimum Sum at a much faster rate than how we are able to save in our CPF, then you will see that something is really wrong here.

Where over the past 20 years, the average net CPF balance that Singaporeans have inside our CPF is continuously lower than the CPF Minimum Sum set by the government, the government would know that the large majority of Singaporeans simply do not have enough to even meet the CPF Minimum Sum! Then, why do they keep increasing the CPF Minimum Sum, and not only that, but increase it at a faster rate!

I had also asked the Manpower Minister if the government would consider increasing the wages of Singaporeans and the CPF interest rates. However, the government bypassed these questions.

Where is the political will to enact the changes necessary to improve our CPF, to protect Singaporeans?

Do you see it?

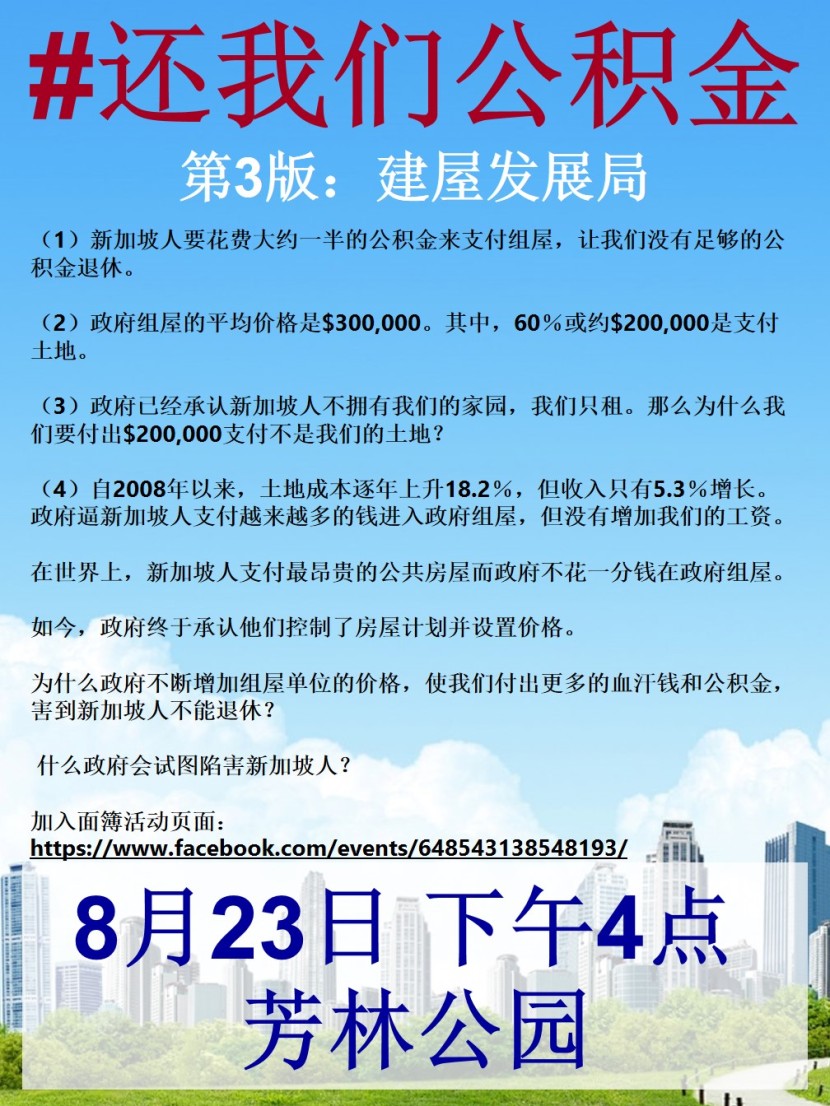

3rd Edition Of The #ReturnOurCPF Event: Why Singaporeans Cannot Retire Because Of The HDB

It is perhaps time to stop sitting back. The CPF is our hard-earned money but we no longer know what is going on with it, let alone know if it is still our money. If we don’t take a stand and demand for answers, our CPF might soon be taken away from our hands and we wouldn’t even know it, until it hits us.

On 23 August, we will be organising the third edition of the #ReturnOurCPF event. In the first edition on June 7, we revealed to you the truths that the government has finally admitted to how they are using our CPF to invest in the GIC. In the second edition on 12 July, we exposed further truths about the exact number of Singaporeans who were not able to meet the CPF Minimum Sum.

Join us at the third edition and take a stand. We know the problems to the CPF, and we know the solutions. But if the government refuses to acknowledge these but chooses to continue telling only their version of the story, then it is time we make our voices heard. It is time we let them know that we know what they are doing and will no longer allow them to put a blindfold around our eyes.

On 23 August, we will see you at Hong Lim Park. Let’s come together, be united and speak for change, for the better for our lives, and our children’s.

You can join the Facebook event page here.

Also, my first court case will be held on 18 September 2014, at 10.00am. It will be a full-day hearing.

Roy Ngerng

*The writer blogs at http://thehearttruths.com/